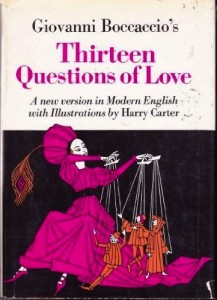

I love love, and I love (for the most part) teaching and reading about love, especially when such involves the work of a ‘master’ of love such as Sappho, Ovid, Hafiz, Stendhal, or Octavio Paz. Giovanni Boccaccio, the ‘third leg’ of the great Italian humanist triad after Dante and Petrarch, certainly belongs in such esteemed company. His Decameron, with its earthy tales of human passion and trickery, is a worthy heir of the great Roman poets of love. After the desultory and disappointing Dead Sea Scrolls, I turned to a slim volume of Boccaccio’s less-famous treatise, Questioni d’Amore, or Thirteen Most Pleasant and Delectable Questions of Love, penned in 1336, when the author was a mere 23 years old. In fact, Questoini is only a small chapter of a much larger youthful work entitled Filocolo, which might be considered the first novel of modern Europe.

I love love, and I love (for the most part) teaching and reading about love, especially when such involves the work of a ‘master’ of love such as Sappho, Ovid, Hafiz, Stendhal, or Octavio Paz. Giovanni Boccaccio, the ‘third leg’ of the great Italian humanist triad after Dante and Petrarch, certainly belongs in such esteemed company. His Decameron, with its earthy tales of human passion and trickery, is a worthy heir of the great Roman poets of love. After the desultory and disappointing Dead Sea Scrolls, I turned to a slim volume of Boccaccio’s less-famous treatise, Questioni d’Amore, or Thirteen Most Pleasant and Delectable Questions of Love, penned in 1336, when the author was a mere 23 years old. In fact, Questoini is only a small chapter of a much larger youthful work entitled Filocolo, which might be considered the first novel of modern Europe.

The story in Questioni, as in other parts of the larger novel, is rooted in autobiography, specifically Boccaccio’s infatuation with a woman named Maria d’Aquino, whom the author first glimpsed on Holy Saturday, 1336, as he lounged with his pals on the steps on the church of San Lorenzo in Naples. She was, in a word, his Beatrice, his Laura (or his Yvonne, of Le Grand Mealnes fame; more on this later). And yet, as Harry Carter, illustrator of my edition of Questioni (a reprint of H.G.’s flawed 1566 translation), adds: “This was to be no spiritual union, such as satisfied Dante with his Beatrice, nor was it to be the idealized and romantic love of Petrarch for Laura. Boccaccio’s desires were of the flesh and he pursued them with the single intention of consummation.” Now, there is some truth in this – compared with his two towering forebears, GB’s prose tends, as noted, towards the Ovidian. And yet, the tone of disapprobrium is not only overly moralistic for my tastes, it also misses the possibility that one can be both ‘spiritual’ and fleshly’ at the same time. In other words, it buys too-readily into the Platonic-Christian dualism that runs against, in my humble opinion, the way most folks actually feel when in love (and by ‘love’ here I mean ἔρως in the full, original, Greek sense).

So what of the tales themselves? A few are of interest, though they lack the sophistication or the tales of the Decameron, perhaps betraying the author’s youth. I do appreciate, however, that GB lets women tell half the tales, and generally avoids making their stories ‘gendered’. And while I personally disagree with most of the advice given by ‘Queen’ Fiammetta (who stands in for Maria d’Aquino), her logic is generally sound. Certainly, the most interesting chapter is in the very middle, where Galeone asks Fiammetta whether love is “a good or evil thing.” Galeone asks this while gazing, enraptured, at his interlocutor, which clearly colors her reply. In the end, she concludes: “Truly, if it were lawful we would willingly live without Love. But of such a harm we are too late aware. And since we are caught in his nets, therefore until the light that guided Aeneas out of the dark ways as he fled the perilous fires may appear to us, it is better for us to follow him and be guided submissively to his pleasures.”